June 30, 2023

The Honourable Marco Mendicino

Minister of Public Safety

House of Commons

Ottawa, Ontario

Dear Minister,

In accordance with section 192 of the Corrections and Conditional Release Act, it is my privilege and duty to submit to you the 50th Annual Report of the Correctional Investigator.

Yours respectfully,

Ivan Zinger, J.D., Ph.D.

Correctional Investigator

Table of Contents

Correctional Investigator's Message

Thematic Investigations and Inspections

Thematic Investigation: The Rising Cost of Living Behind Bars

Thematic Inspection: Dry Cells

National Updates

Patient Advocacy Services in Federal Corrections

Gender Diversity Policy Review

Minimal Options for Federally Incarcerated Women in Minimum Security Units

Fifth Independent Review Committee on Non-Natural Deaths in Custody

Ten Years since Spirit Matters: Indigenous Issues in Federal Corrections (Part II)

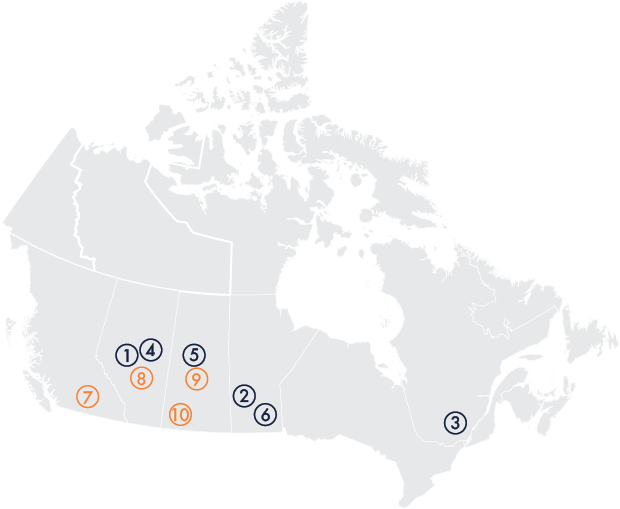

Unfulfilled Promises: Investigation of Healing Lodges in Canada’s Federal Correctional System

A Straight and Narrow Road: An Investigation into CSC’s Pathways Initiatives

An Investigation of the Role and Impact of Elders in Federal Corrections

Correctional Investigator’s Outlook for 2023-24

Ed McIsaac Human Rights in Corrections Award

Correctional Investigator's Message

The Office of the Correctional Investigator celebrates its 50th Anniversary in June 2023. Anniversaries are moments for reflection and the celebration of achievement. I am extremely proud of the fact that this little office with an outsized mandate has served and stood the test of time for half a century now. I am deeply privileged, in my capacity as Correctional Investigator, to offer a few personal reflections about an extraordinary place that has been my home for most of my professional career.

As I often share with people who are unfamiliar with our work, the Office or OCI, was created out of the trials and tribulations that nearly brought Canada’s penitentiary system to its knees in the early 1970s. The origins of the Office lie in a system that failed to provide incarcerated people with an external and independent outlet to raise and redress legitimate grievances. Today, serving as a prison oversight and ombudsman body for federally sentenced persons, the OCI remains as vital and focused as ever on this core mandate.

Since its creation, the Office has answered hundreds of thousands of calls and resolved tens of thousands of complaints. Cumulatively, over the Office’s half century of operations, our investigative staff has literally spent years inside federal institutions. At a more macro level, the Office is part of an overall network of oversight and accountability that provides some level of assurance that people serving a sentence of two years or more are treated fairly, lawfully and humanely. In a system that has periodically tolerated abuse and impunity, the Office is the eyes and ears of transparency.

I first joined the Office in 2004, then serving as Director of Policy and Legal Counsel. As I recall, the Office was not all that well known and struggled to be heard. A new Correctional Investigator – only the third in the history of the Office up to that point and my immediate predecessor – Mr. Howard Sapers, was appointed in April 2004, a role he would keep for the next 12 years. To his enduring credit, Howard steered the Office through a challenging transition period and into an era of increased visibility and influence. Under his leadership, the Office brought attention to mental health concerns in corrections, initiated public coverage of preventable deaths in custody, raised concerns around safe and humane custody and produced more focused yearly reporting on issues facing federally sentenced Indigenous people and women in federal custody. A series of public interest reports during those years highlighted the experience of a diverse range of incarcerated people including the elderly, young adults, individuals with mental health issues, gender diverse and Black persons. These individual and systemic areas of concern remain some of the hallmarks of Office reporting to this day.

More recently, and since my first appointment as Correctional Investigator in January 2017, the Office has continued to raise and report on issues and incidents of national significance in Canadian corrections. Fatal Response: An Investigation into the Preventable Death of Matthew Ryan Hines was tabled as a Special Report to Parliament on May 2, 2017. Since then, the Office completed a series of major investigations updating findings from previous reports and reviews including:

- Missed Opportunities: The Experience of Young Adults Incarcerated in Federal Penitentiaries (August 2017).

- Aging and Dying in Prison: An Investigation into the Experiences of Older Individuals in Federal Custody (February 2019).

- Update on the Experiences of Black Persons in Canadian Federal Penitentiaries (2021-22 Annual Report).

In the last few years, the Office conducted two ground-breaking investigations: A Culture of Silence: National Investigation into Sexual Coercion and Violence in Federal Corrections (2019-20 Annual Report), followed up by a review of Uses of Force Involving Federally Incarcerated Black, Indigenous, Peoples of Colour (BIPOC) and Other Vulnerable Populations (2020-21 Annual Report). This year’s Annual Report features Part II of our update of the original 2013 Spirit Matters 1, which completes a historic two-year investigation examining the over-representation of Indigenous people in federal corrections.

Along the way, we have published significant compliance reviews, case studies and findings on any number of issues of public interest and concern in federal corrections:

- Quality and Quantity of Prison Food

- Riot at Saskatchewan Penitentiary

- Over-representation of Indigenous Women in Maximum Security

- Alternatives to Incarceration for Seriously Mentally Ill Persons

- Education behind Bars

- Solitary Confinement (Administrative Segregation)

- Medical Assistance in Dying (MAiD) in corrections

- Use of Pepper Spray in Use of Force Interventions

- Prison Needle Exchange Program

- Mother-Child Program in Women’s Corrections

Each of these represents collective achievement and accomplishment. I am fortunate and honoured to lead an Office that, from its earliest days, has strived for excellence in investigative reporting.

Continuing in a rich and proud tradition of producing timely, innovative and compelling public reporting, this year’s collection of issues includes a thematic look at the history of inmate pay in federal corrections from 1981 to the present. As I note in this piece, this topic is an area of perennial concern for incarcerated people reaching back to the Office’s earliest days. Incredibly, a federally sentenced person received a higher real daily wage for participating in prison work in 1981 than the current rate of pay that tops out at $6.90 per day. The contemporary financial and pay system has been stripped of all incentive, bearing little resemblance to its original form or intentions. Earning less than 46 cents an hour, the current pay system keeps people behind bars destitute, demeaned and degraded. Furthermore, it contributes to tensions and violence inside penitentiaries, which has a significant negative impact on both correctional staff and incarcerated persons. It is broken and dysfunctional, serving no redeeming correctional or public safety interest, and is in desperate need of a major overhaul.

Our inspection-based investigation of dry cell detention policy and procedure follows up on last year’s reporting on this issue, and yields some surprising findings, especially in light of recent interventions by the courts, Parliament and even the Minister of Public Safety. Other updates in this year’s report include gaps in gender diversity policy, the under-utilization of minimum-security units in women’s institutions, findings from the fifth Independent Review Committee on non-natural deaths in custody, and the outstanding legislated requirement for the Correctional Service to provide access to external and independent Patient Advocacy Services.

In this year’s Annual Report, a higher than usual number of my recommendations are directed to the Minister of Public Safety rather than the Correctional Service of Canada. This is deliberate and consistent with section 180 of the Corrections and Conditional Release Act (CCRA), which directs that I shall provide notice and report to the Minister of Public Safety whenever the Correctional Service of Canada (CSC) does not, within a reasonable time, take adequate or appropriate action to address findings and recommendations of my Office. To meet this obligation, in this year’s report I am directing a number of outstanding issues to the attention of the Minister, including offender payments, dry cell detention, patient advocacy, convening of independent investigations into incidents and interventions resulting in death behind bars, along with other significant areas that fall under Indigenous Corrections. My expectation is that elevating issues where there has not been adequate response or resolution will result in more measureable and substantive progress.

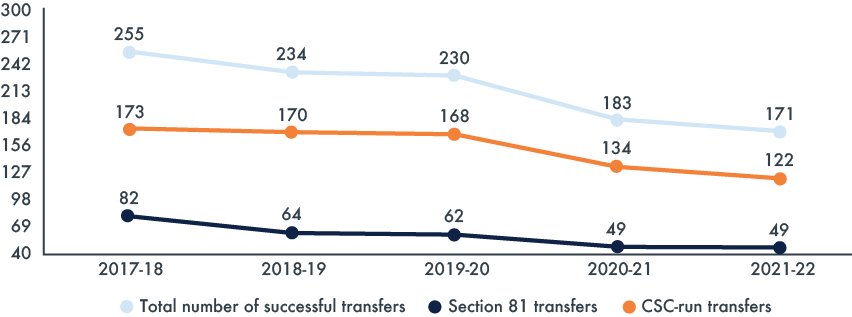

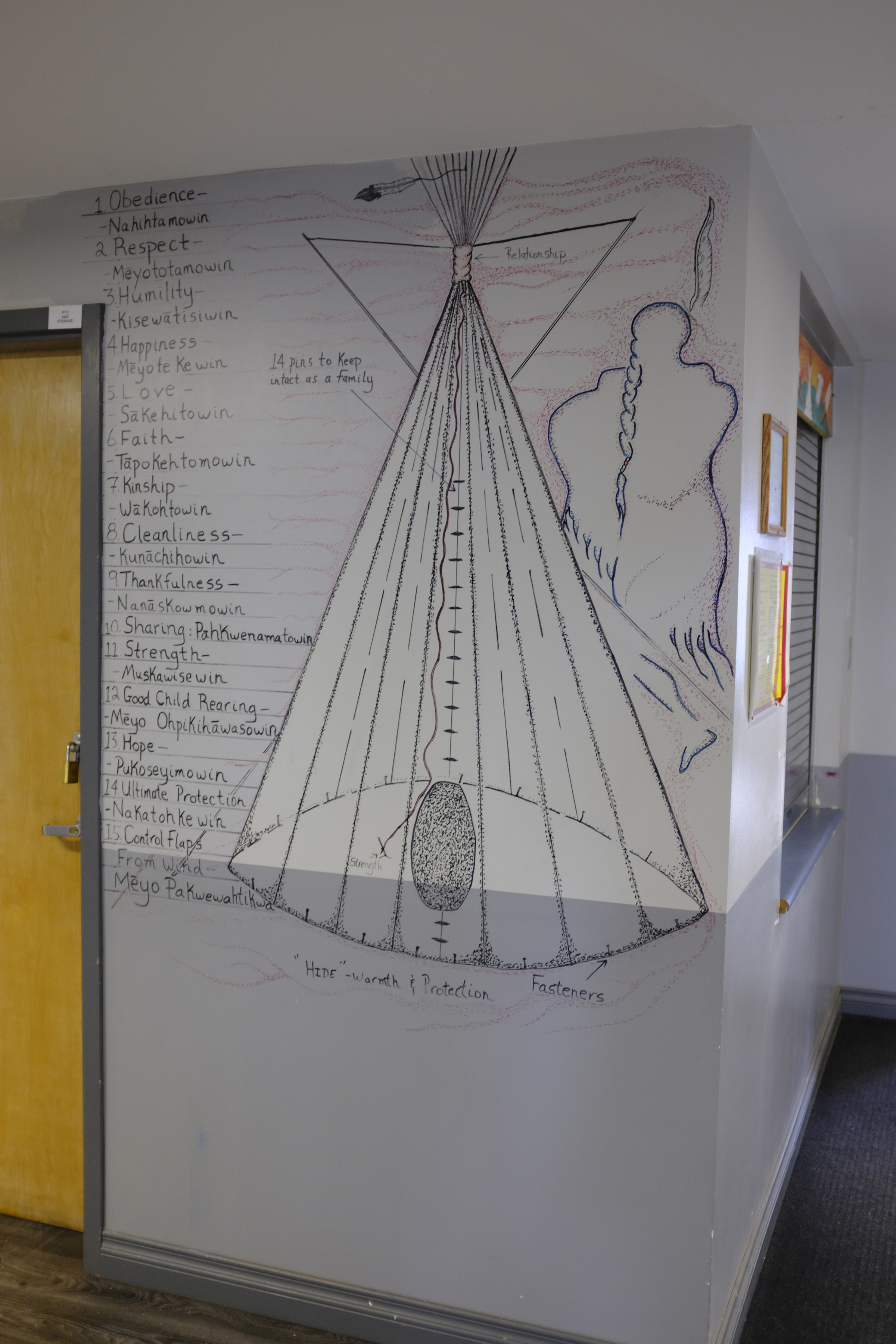

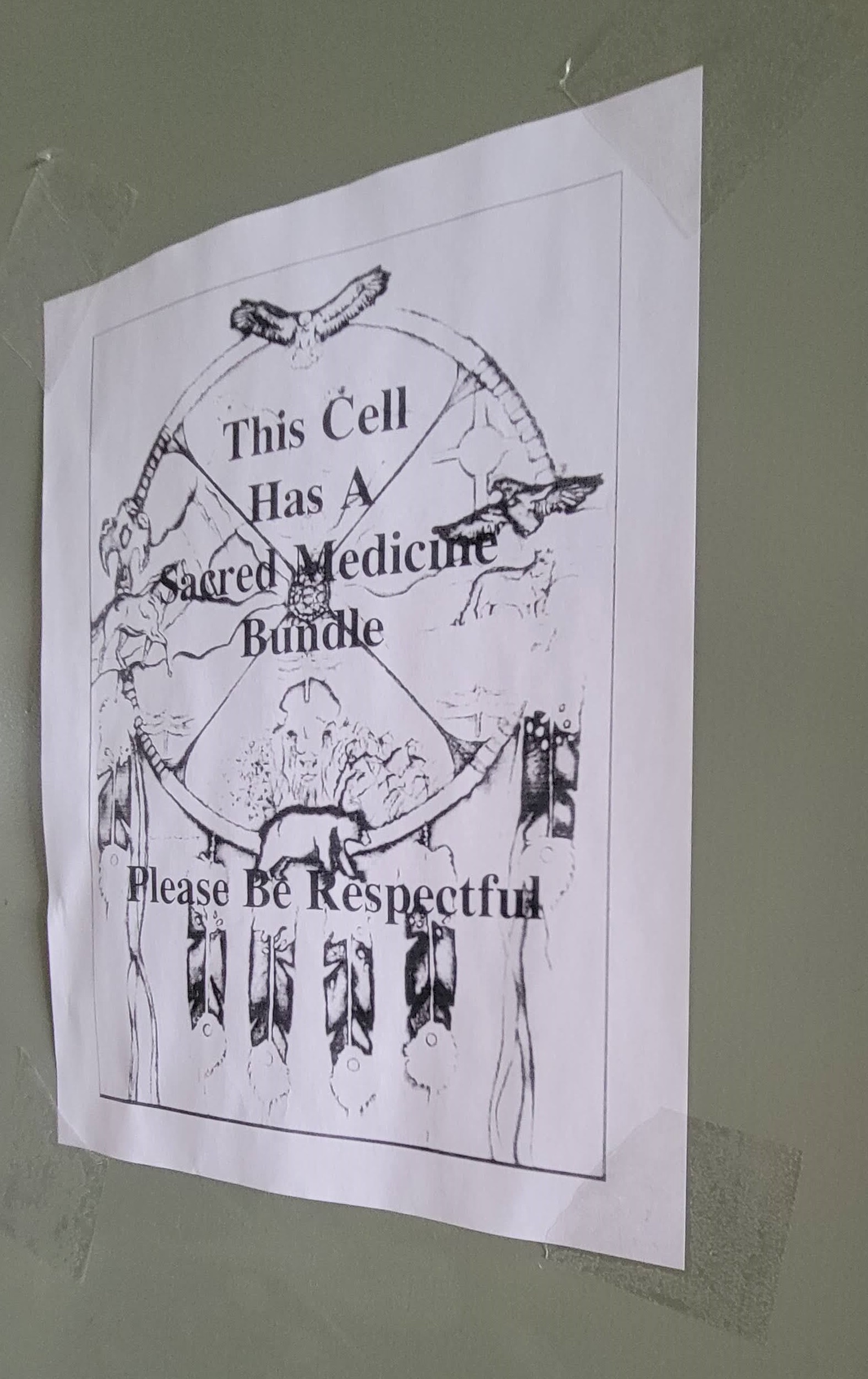

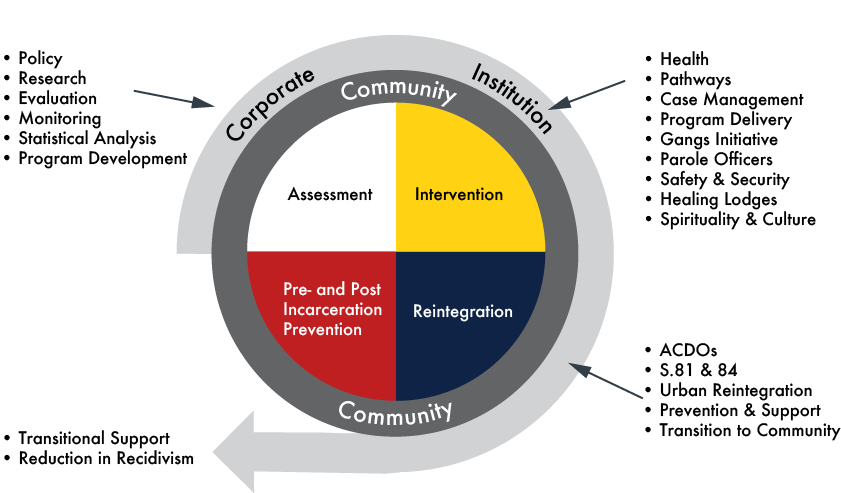

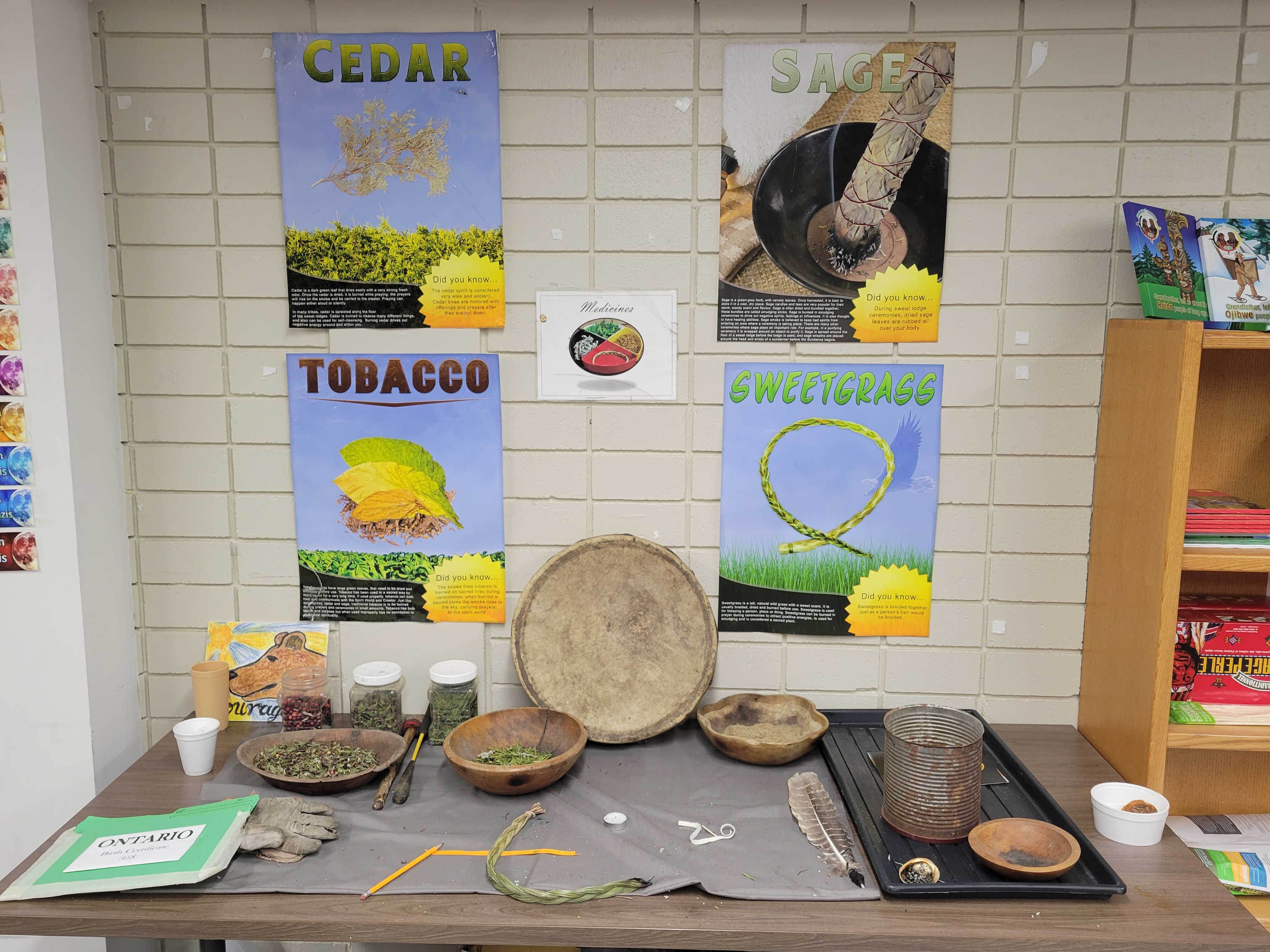

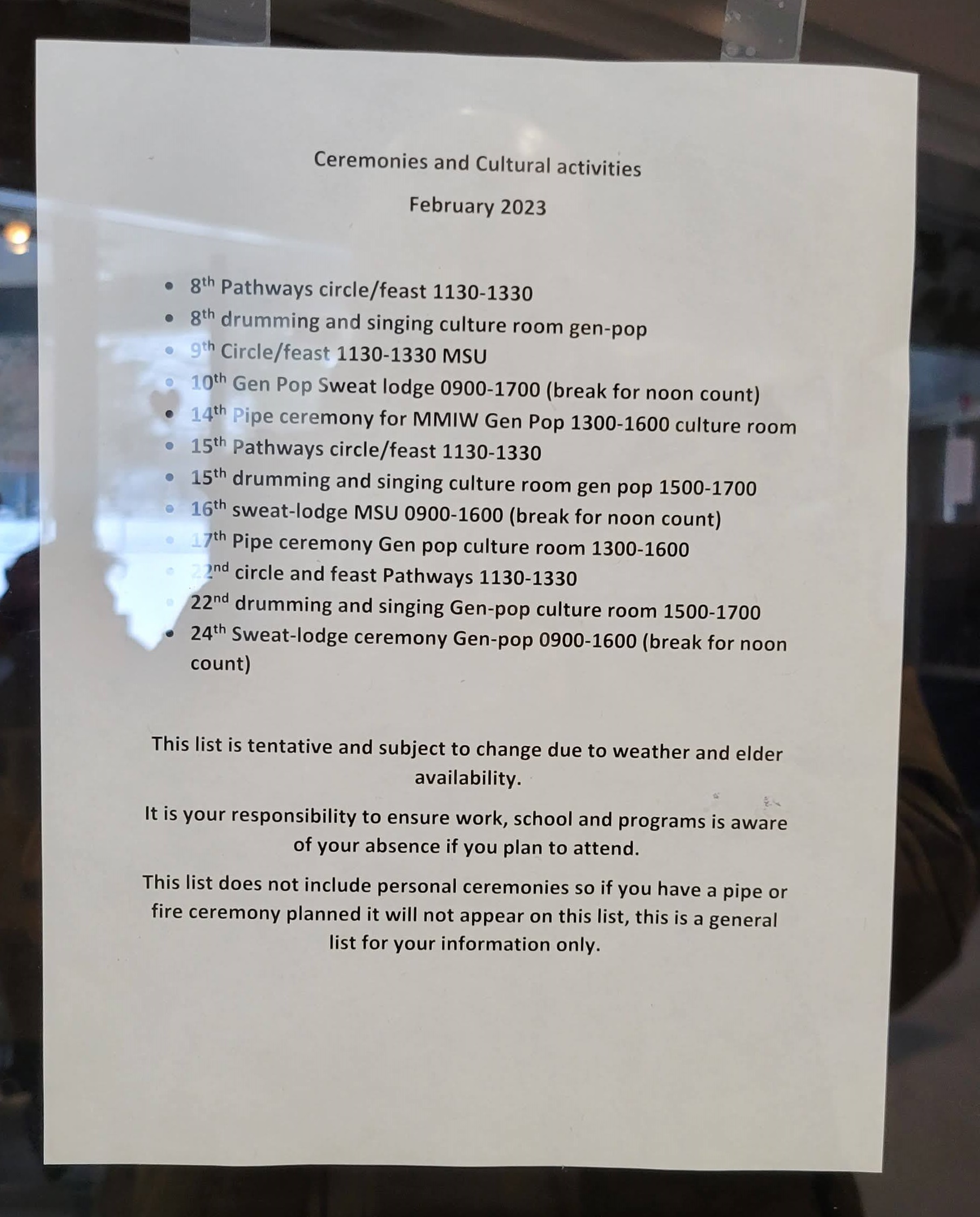

As mentioned, the major piece of this year’s report is our investigation into the over-representation of Indigenous people in Canadian prisons. It is an issue of documented concern for this Office ever since the appointment of the first Correctional Investigator, Ms. Inger Hansen, in 1973. In this investigation, we deliberately set out to document the often-missing voices, experiences and testimonies of Indigenous people who work or live inside the system. We met with many Elders to hear about their experience with providing ceremony, healing and guidance to their ‘relatives’ behind bars. We visited and heard from participants in Pathways, a penitentiary-based initiative that offers healing to Indigenous people. We visited community Section 81 and state-run Healing Lodges to compare and draw lessons learned. We also engaged with stakeholders, advocates, and leaders of national Indigenous organizations.

In distilling what we heard and witnessed, our findings are many and significant. Despite the diversity of views and perspectives, there was often convergence on a few key points:

- CSC is failing to make the kind of innovative policy and resource changes that are required to address factors within its control to mitigate and reduce the chronic over-representation of Indigenous people.

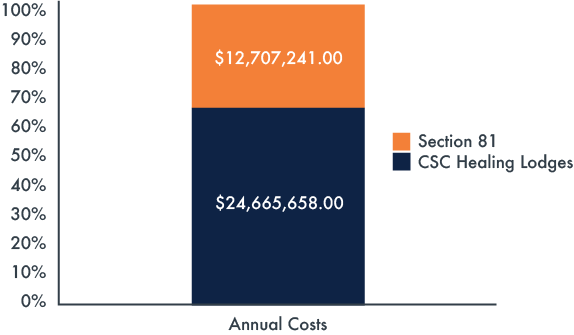

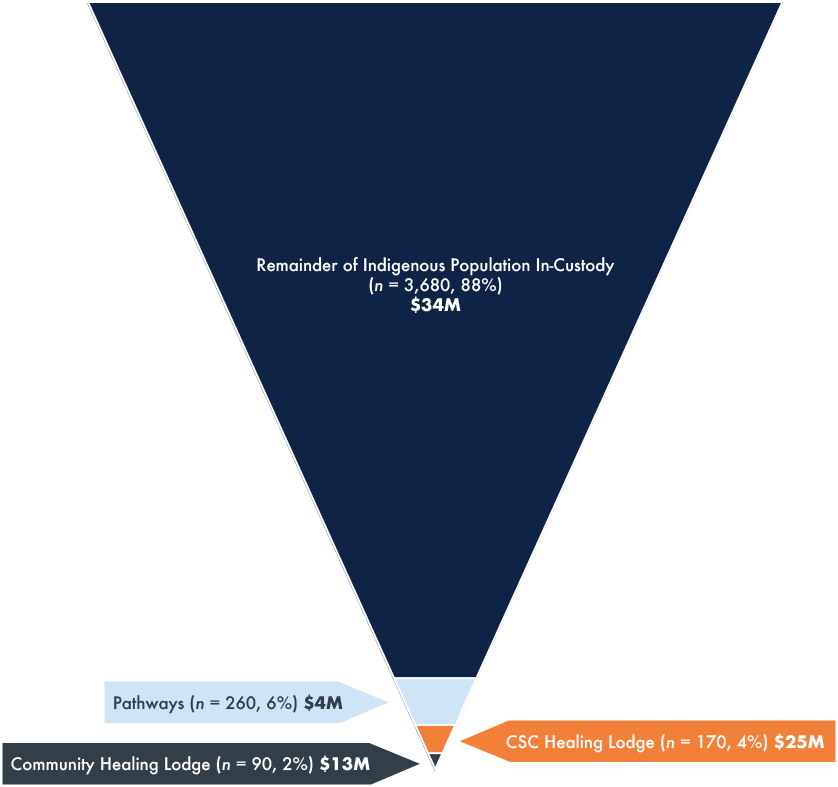

- State-run Healing Lodges are funded, staffed, resourced and occupied at significantly higher levels than their Section 81 community counterparts.

- The contributions of Elders are under-valued, under-reported and under-supported by their CSC employer.

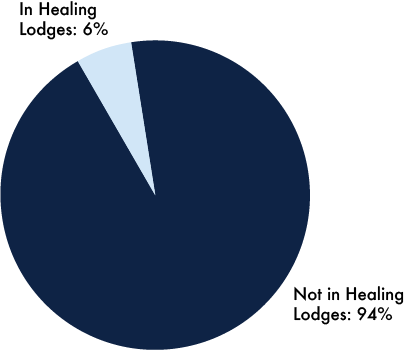

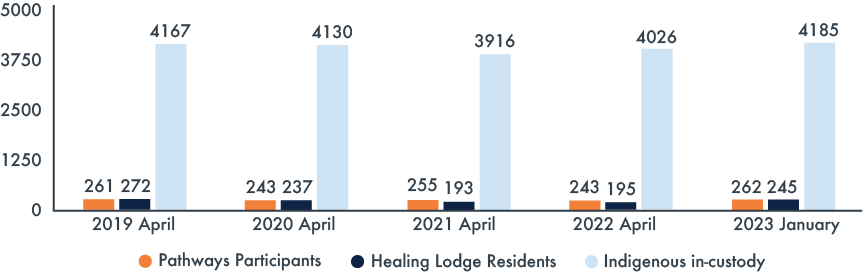

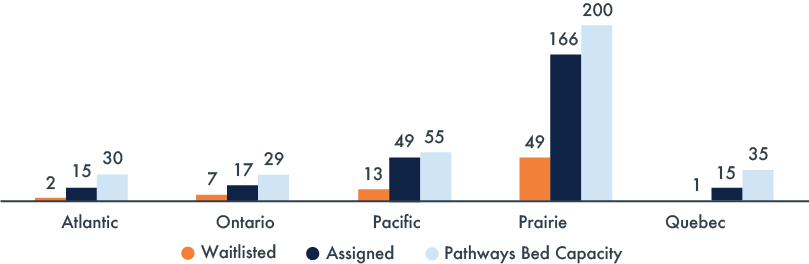

- Signature interventions in CSC’s Indigenous continuum of care strategy, such as Pathways Initiatives and Healing Lodges, serve such a small minority of federally sentenced Indigenous people that they have no meaningful or measureable impact on over-representation.

- CSC’s pan-Indigenous approach to Indigenous Corrections erases significant historical and cultural differences between and among First Nations, Métis and Inuit leading to significant gaps and omissions.

Looking back on the legacy of over-representation in this country is also an opportunity to anticipate a much brighter future. Canada’s relationship with Indigenous people requires reckoning with the legacy of our colonial past and walking along the path of reclamation and reconciliation in the present. Canada’s federal correctional system needs to get on board and begin to divest itself of the authorities, controls and resources that have kept Indigenous people over-incarcerated for far too long. I believe that the findings and recommendations of this report, if actioned, provide part of the blueprint for change and transformation. In the spirit of reconciliation, it is my intention to compile and publish Part I and Part II of Ten Years Since Spirit Matters into a single compendium following tabling of this year’s Annual Report in Parliament.

Finally, in marking the OCI’s 50th Anniversary, over the coming year we intend to host a few public engagements, relaunch and rebrand our website, develop and share new materials celebrating our history. As we reflect on our many accomplishments over the last half century, in the here and now I must pay tribute to my talented and amazing staff members who share a common commitment to serving our mandate with excellence.

Ivan Zinger, JD., Ph.D.

Correctional Investigator

June 2023

Executive Director’s Message

This past year we have returned a bit more to our regular way of working after three years of a global pandemic. Thankfully, the lockdowns in federal correctional institutions, as a result of Covid outbreaks, are now seen in the rear view mirror. Although the virus is still with us, we are implementing an incremental return to the Office for all employees. As a result, we were able to return to our regular schedule of visits to institutions. We also conducted our systemic investigations with hundreds of interviews with incarcerated persons, staff and stakeholders proceeding in-person. We all acknowledge the positive impact in-person meetings and visits bring, where human connection is enhanced. As we transition back to the Office, we recognize the benefits of face-to-face interactions with our clients and colleagues.

The Office is at a pivotal point in its history as we celebrate 50 years in 2023 since the OCI first opened its doors. The work we do as a correctional oversight agency is as important as it ever was and continues to provide a necessary and invaluable function in a healthy democracy.

We have begun the implementation of the four pillars of our 3-5 year Strategic Plan: 1- OCI Employer of Choice (Health and Well Being), 2- Renewed Organizational Structure (Support nimble organization, career progression and talent management) 3- Systemic Investigations and Inspections (support planning process and inspection model), and 4- Development and Implementation of Data and Performance strategy (support reporting obligations). As part of our organizational modernization, we have worked to redesign and improve accessibility of our Website, which will be re-launched as part of our 50th anniversary celebrations.

The work undertaken to implement our Strategic Plan led us to the conclusion that the Office was in dire need of additional resources. In the last year, we dealt with 4,897 complaints and spent 227 days in institutions where we conducted 1,270 interviews with federally incarcerated persons. Many of our calls and interviews are with individuals who suffer from mental illness, trauma, addictions, and the consequences of childhood abuse. It has become clear that our employees need to be better supported to manage a more complex and challenging caseload, and that our investigative model should better comply with international standards for prison oversight mechanisms, including limiting the number of institutional visits investigators conduct alone. We realized that the current resource allocation also does not allow for a sustainable corporate services structure in a micro agency, with the same number of reporting requirements to Central Agencies as much larger departments. I am happy to say that the Office was successful in its request for new permanent funding which will allow for better support to employees and more effective and accessible services for federally incarcerated individuals. This new funding speaks to the positive impact of this Office and the confidence and credibility it has with Parliamentarians and Canadians alike.

The focus of this year’s Annual Report, Ten Years Since Spirit Matters: Indigenous Issues in Federal Corrections (Part II), speaks to the Office’s continued commitment to address the shameful over-incarceration of Indigenous populations in this country. The systemic racism and discrimination suffered by Indigenous peoples, often baked into policies, programs, and laws is one of the most pressing human rights issue in Canada.

As we all commit to reconciliation as well as fair and humane corrections, I appreciate the collaboration between the Office of the Correctional Investigator and the Correctional Service of Canada. Collaboration is important in flagging and addressing problem areas for the Service, and equally for the Government of Canada, as we all work to ensure better correctional outcomes in this country.

As always, I very much value the team of dedicated experts I have the opportunity to work with each and every day in order to fulfill our important mandate as oversight agency of ensuring the voices of those behind bars are heard, and addressing and bringing attention to unfair treatment and violations of human rights.

Monette Maillet

Executive Director and General Counsel

Thematic Investigation: The Rising Cost of Living Behind Bars

Introduction

My Office has raised the issue of an inadequate and antiquated Offender Program Assignments and Inmate Payments program (Inmate Pay)2 multiple times in previous public and media reporting, including a recommendation that the Minister of Public Safety initiate a review of the system in our 2015-16 Annual Report.3 More recently, I raised the matter in a February 10, 2023 appearance before Parliamentary members of the Standing Committee on Public Safety and National Security.4 At issue here is a payment and allowance system that is so fundamentally flawed that it fails to substantively meet its primary legislative and policy objective, which is to encourage participation in programs, vocational and work opportunities behind bars. Since 1998, the point in time when the former pay program was directly linked to participation and performance in programs specified in a correctional plan, there has been a steady and accelerated erosion of purchasing power behind bars.

Today, the impact of a series of cost of living increases including, the rising costs of canteen and consumer goods, mandatory deductions from pay, elimination of incentive pay for work in prison industries, requirement to purchase items that were previously standard issue and wages not indexed to inflation, has led to an environment of scarcity and insecurity behind bars. Many sentenced individuals live near or in a constant state of impoverishment and destitution, inside and outside prison. Moreover, the deprivations of an inadequate pay system feed a prison underground economy of violence, extortion and abuse that jeopardizes the safety and security of everyone. So far removed in purpose from its original intent, the current payment and allowance system serves no redeeming correctional or public safety interest and demands to be reformed as a matter of urgency and priority.

The ‘New’ Inmate Pay Program of 1981

In understanding how we got to this unfortunate situation, it is perhaps instructive to revisit the contemporary origins of the payment and allowance system in federal corrections.5 The current rates of pay, which tops out at $6.90 per day before deductions, tracks back to 1981 when the forerunner to today’s pay system was introduced in federal corrections.6 At that time, the sliding wage scale for penitentiary work was linked to the daily disposable income of a single wage earner receiving the federal minimum wage, which in 1981 was $3.50 per hour. The daily disposable income rate, which is a measure of the amount of money remaining to an individual after paying income tax, room and board, Canada Pension contributions, clothing, education, transportation, etc., was established at a rate of $3.15 per day. In 1981, this figure became the standard lowest rate of daily pay for a working individual at a maximum-security institution. This minimum rate of pay, linked to disposable income, was considered reasonable and fair at the time given that the costs for items such as shelter, food, medical needs, furnishings and education were already born by the federal Correctional Service. In most cases, the implementation of the new pay program in 1981 resulted in a substantive increase in wages. As it happens, it was also the last time that pay for federally sentenced persons was increased.

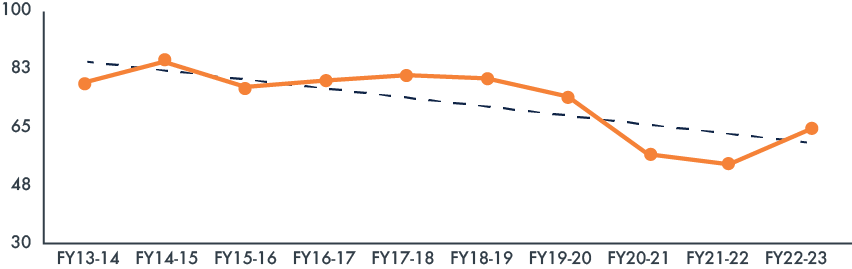

Unlike today, the pay scales adopted in 1981 had monetary rewards and incentives baked in, and included a system of incremental increases linked to security level. A similar, but slightly lower daily payment structure was also adopted for those engaged in education and vocational training programs. As depicted below, the 1981 pay program topped out at $7.55 per day for an individual working in a minimum-security institution. In today’s valuation, adjusting for inflation and the consumer price index, that figure stands at $23.07 per day.

Table 1. The 1981 Correctional Service of Canada Pay Program by Security Level

PAY LEVEL | MINIMUM | MEDIUM | MAXIMUM |

1 | $1.60 | $1.60 | $1.60 |

2 | $4.80-5.35-5.90 | $3.70-4.25- 4.80 | $3.15-3.70-4.25 |

3 | $5.35-5.90-6.45 | $4.25-4.80-5.35 | $3.70-4.25-4.80 |

4 | $5.90-6.45-7.00 | $4.80-5.35-5.90 | $4.25-4.80-5.35 |

5 | $6.45-7.00-7.55 | $5.35-5.90-6.45 | $4.80-5.35-5.90 |

Under the system introduced in 1981 it was very possible, and indeed encouraged, for an individual to put money away in a savings account to support their eventual release, and/or to send money out to family or loved ones in the community. Back then, though there were some mandatory deductions taken from earnings (e.g. Inmate Welfare Fund deduction was 10 cents per day and another 30 cents for recreational and entertainment purposes), their overall bite pales in comparison to today. Moreover, as we have seen, the original 1981 pay structure already factored in room and board and phone deductions unlike today where sentenced individuals are required to forfeit 30% of their income to offset these costs.

With the introduction of the Corrections and Conditional Release Act (CCRA) in 1992, the Correctional Service of Canada (CSC) was obliged to align its payment and allowance program to the requirements of the new Act. Given its overall focus on rehabilitation and reintegration, relevant CCRA provisions directed that payments to offenders should encourage their participation in programs (inclusive of correctional, vocational, educational and work opportunities). Accordingly, in 1998, reflecting the CCRA’s more progressive aims, CSC implemented new policy criteria and promulgated a new Commissioner’s Directive (CD), which today is still titled Offender Program Assignments and Inmate Payments (CD 730). In essence, the new CD redefined the criteria and expectations of participation, but mostly retained the former 1981 pay rates, with a few notable exceptions. For example, the new Level C pay rate corresponds with the former Level 3 pay and Level D pay corresponds to former Level 2. The new daily allowance rate for incarcerated persons who are unable to participate in program assignments for reasons beyond their control was increased to $2.50 from the former Level 1 rate of $1.60. A Basic Allowance of $1.00 per day was added for those who refuse to participate in any program assignment.

More controversially, and the source of so much of today’s frustrations, complaints and problems behind bars, the revised pay structure added two entirely new top levels of pay (Levels A and B). In introducing the criteria for these levels, a revoked Policy Bulletin from 1998 indicates that individuals will have to meet “more exacting performance standards to earn pay at the two top levels.” The current and still unchanged assessment criteria for Level A pay are indeed “exacting,” as detailed below:

CD 730 – Offender Program Assignments and Inmate Payments. Annex B, Section 1.

Level A ($6.90) will be awarded to inmates who have been earning level B for at least the previous six months or are already earning level A and have met the following criteria for at least the past six months:

- no unauthorized absences

- no unjustified late arrivals to, or early departures from, the program assignment

- no convictions for disciplinary offences

- a high level of accountability, motivation and engagement […]

- have not been placed in a specialized unit (Special Handling Unit, segregation for disciplinary reasons, etc.)

- are not affiliated with a security threat group […]

- full and active participation in all aspects of their Correctional Plans

- exceeded all expectations of the program assignment

- exceeded expectations for interpersonal relationships, attitude, motivation, behaviour, effort, productivity and responsibility

As outlined in Table 2, only 4.6% of the current incarcerated population makes the maximum daily rate of Level A ($6.90). Due to a sliding scale of restrictive eligibility criteria for the different pay levels, the largest proportion of the population (50%) earns Level C pay, which is $5.80 per day. Although the COVID-19 pandemic has likely had an impact on the unequal distribution of pay, the Office has recorded relatively low proportions of the population meeting the “exacting” behavioural expectations of Level A and B pay grades.7 More recently, I have reported on discrepancies in pay levels specifically for incarcerated Black individuals.8

Table 2. Proportion of the Federally Incarcerated Population at Each Authorized Level of Payment or Allowance (FY 2022-2023)

| PAY/ALLOWANCE LEVEL | AMOUNT PER DAY | PROPORTION OF THE FEDERALLY INCARCERATED POPULATION |

A | $6.90 | 4.6% |

B | $6.35 | 18.0% |

C | $5.80 | 50.8% |

D | $5.25 | 6.8% |

Allowance | $2.50 | 19.0% |

Basic Allowance | $1.00 | 0.1% |

Zero | $0.00 | 0.9% |

Source: CSC Data Warehouse (March 3, 2023).

This history lesson in prison economics is important because it contains insight into how current payment and allowance rates were derived, and how much they have degraded over time. Essentially, rates of pay have not fundamentally changed since 1981, though the eligibility requirements and behavioural expectations associated with them have been substantially altered. Pay levels for the federal incarcerated population have never been adjusted or indexed to inflation, and have never been tied to the Consumer Price Index. As time passes, there has been an inevitable and progressive decline in purchasing power as the costs of goods increase and wages stagnate and erode.

Other policy and politically-motivated decisions have left their own historical legacy, as, for example, when in 2013 incentive pay for overtime and work in prison industries was eliminated, and room and board (22%) and administrative costs of the telephone system (8%) were added to the list of mandatory deductions from pay envelopes. In the example below, we estimate that an individual receiving the most ommon level of pay after mandatory deductions will have net (or “take home”) earnings of about 46 cents an hour. Beyond violating every principle of any labour code, such a miserly amount is an affront to human decency and dignity and may very well contravene Canada’s international human rights standards, including the Nelson Mandela Prison Rules (United Nations Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners).

As we have seen, the CCRA alignment of pay scales was intended to encourage or incentivize participation in programs (as opposed to paid work). Today, the behavioural expectations and standards that are tied to the top payment allowance levels are so exclusionary and restrictive that the overwhelming majority of the population is effectively disqualified, simply unable, or just unwilling to meet. The assessment criteria is almost entirely subjective and discretionary in nature, and can be used against an individual, with little recourse for appeal. Today, the majority of the population “chooses” to do the bare minimum required (Level C pay – participation in a program assignment) and almost as many effectively opt out or do not meet the criteria. The net “take” home or difference in the “enhanced” pay levels (A and B) is simply not worth the effort to be compliant and it is unrealistically achievable within the context of a federal institution. Perversely, a system that was supposed to encourage participation in programs and other opportunities behind bars, to engage in core components of one’s correctional plan, has become its own singular disincentive to engagement. Over time, other elements of the inmate financial system have become equally subject to neglect. We are left with a system that has digressed from its primary objective and is so distorted and that it serves virtually no correctional purpose.

Deductions

According to CD 860 – Offender Money, the following deductions are to be taken from an individual’s income.

This example uses a 14-day pay period, with a maximum of 10 days of work (at approximately 6 hours a day) for the most common level of pay - $5.80 per day, or $58.00 per pay period.

- 22% for food and/or accommodation = $12.76

- 8% for the administration of the telephone system = $ 4.64

- 1-2% for the Inmate Welfare Fund9 = $0.58-$1.16

- 10% for Court-Ordered Obligations = $5.8010

- 10% for mandatory savings = $5.80

Approximate Net Pay

- $27.84 per pay period

- $2.78 per work day

- $0.46 per work hour11

A Case for Revision and Reform

According to CSC policy (CD 860 – Offender’s Money), the current financial system in place for federally incarcerated individuals is meant to encourage them to budget their income for purchases and payments while incarcerated, and to prepare funds for expenditures upon release. Understandably, part of CSC’s approach to managing the administration of finances behind bars is to control the flow of money in the institutions for safety and security reasons. Accordingly, there is no use of cash in the institutions; all transactions are based on credit via a dual-account system.

As outlined in the Corrections and Conditional Release Regulations (CCRR; Section 111), an ‘Inmate Trust Fund’ is established for each federally sentenced individual, consisting of two different accounts: a current account for regular daily expenditures and a savings account for longer-term budgeting. Using this account system, each individual is responsible for their personal budgeting to ensure availability of funds for a range of purchases, including:

- court ordered obligations

- personal identification (e.g., birth certificate)

- personal expenses and property (e.g., telephone calls, canteen, personal hygiene, personal hobbies)

- correspondence (stamps) and post-secondary courses and related materials

- expenses incurred while on work release or temporary absence

- release or expenses while on release to the community

Ten percent of an individual’s income is automatically deposited into their savings accounts per pay period. Individuals are allowed to transfer money from their savings account to their current account for spending purposes. This normally occurs no more than four times a fiscal year and cannot exceed a total of $750.00 annually, aside from some exceptions that require approval from the Warden (e.g., fees for legal services, use of private family visit units, non-essential medical expenses etc.). The minimum balance for an individual’s savings account is set at $80.00. Upon release, all money credited to an individual in their Inmate Trust Fund is provided to them, following payment of any money owed to the Crown.

Although there are different potential sources of money (e.g., family members can transfer money to their incarcerated loved ones), as we have seen, the primary source of income for most individuals is payments earned from participation in correctional interventions (e.g. programs, employment, vocational training). Since the 1980s, the Consumer Price Index (CPI), which calculates changes in prices in standard goods and services as experienced by Canadians (including costs of food, shelter, transportation, etc.), has increased over 225%.12 According to the Bank of Canada inflation estimates, the maximum pay rate of $6.90 per day now equates to approximately $22.50 in 2023 value terms.13 Adjusting for inflation, this would correspond to $3.75 an hour before deductions. For further comparison, the average minimum wage across Canada in the early 1980s was approximately $3.50-$4.00 an hour; the national average now sits around $15.00 an hour.14 These are clear demonstrations of the substantial gap between pay scales for incarcerated individuals, and the baseline standard of living rate in Canada. Even a small amount of difference can have a large impact on the life of an incarcerated person.

While an in-depth assessment of international practices is beyond the scope of the current analysis, it is worth noting some high-level comparisons. Even though rates of prison pay in Canada may appear better than the United States and somewhat on par with the United Kingdom, we are still behind in comparison to most Nordic and Scandinavian countries.15 Even in comparison to some rates of pay in the provincial/territorial systems in Canada, federal corrections lags behind. For example, in the Quebec provincial correctional system, incarcerated persons engaged in paid employment are remunerated at an hourly rate of approximately 35% of the minimum wage for the province (approximately $5.33 per hour).

In addition to outdated pay levels and restricted eligibility, the policies where pay and monies are implicated (e.g. CD 860 - Offender’s Money and CD 730 - Offender Program Assignments and Inmate Payment) are long overdue for comprehensive review and revision. The former has been in effect since 2014 and the latter since 2016. Moreover, despite some interim policy bulletins that have incorporated some minor updates, the policy suite for the financial system in federal corrections (which includes the Inmate Trust Fund) has remained almost untouched and in force since 1998. In fact, an internal CSC audit of the Inmate Trust Fund, completed in July 2020, recommended that its policy framework (CD 860) be updated.16 Though management agreed to do so, to date it remains an unresponsive and neglected area of CSC interest. In fact, it will likely require the Minister of Public Safety or the Government of Canada, or both, to direct CSC to take much needed action.

COVID 19 – A Special Case?

To its credit, CSC has implemented some offsetting financial measures over the COVID-19 pandemic to ease some of the burden due to work, programming and employment stoppages and/or restrictions. These measures included a pay freeze (April 2020-August 2022) and waiving of fees for food and accommodation and telephone access. CSC also authorized the addition of $5 in funds for phone accounts on several occasions, increased the annual transfer limit from individuals’ savings accounts to their current accounts from $750 to $850, and waived the cost of outgoing faxes to legal counsel. CSC increased total resources for the Small Group Meal Planning (SGMP)17 over the past number of years, and particularly since the pandemic began. Currently, an average of $8.40 per diem is provided (compared to the approximate $5.00 per diem per individual that was provided several years ago).18 I remain fully behind these and other efforts in reducing the burden of cost of living increases. Although these measures were in place at the time of writing, I am concerned that CSC has made it clear that the majority of these offsets are only temporary measures that will eventually be removed.

Cost of Living Increases

To the point of the matter, there is absolutely no denying that Canadians everywhere have felt the sting of cost of living increases and rising inflation, particularly over the past few years.19 Federally sentenced individuals, in prison and in the community, are not immune to the whims of these financial forces. Over the reporting period, my Office has received numerous pieces of correspondence and complaints from incarcerated individuals regarding the rising costs of grocery, personal and canteen items. Given the poor quality and selection of food provided at the majority of correctional institutions that fall under the cook-chill food preparation system,20 individuals continue to rely on purchasing canteen items to supplement their nutritional needs, but even some of these prices are now out of reach. Some more enterprising individuals have made the effort to track prices from the grocery and canteen lists over time to demonstrate cost increases and the impacts of spiraling inflation on their already diminished incomes (see Tables 3 and 4 below).

Table 3. Price Comparison of Selected Items from a House/Pod Grocery List

ITEM | PORTION SIZE | PRICES | PRICES | PRICE INCREASE |

| Chicken Burgers | 2 kg | $9.77 | $14.45 | $4.68 |

| Chicken Thighs | 5 kg | $22.37 | $34.80 | $12.43 |

| Oven Ready Fries | 2 kg | $7.15 | $9.16 | $2.01 |

| Mayonnaise | 890 ml | $4.47 | $9.10 | $4.63 |

| Mustard | 325 ml | $1.10 | $1.50 | $0.40 |

| BBQ Sauce | 455 ml | $1.60 | $2.40 | $0.80 |

| Egg Noodles | 375 g | $2.00 | $2.42 | $0.42 |

| Rice Cakes | 180 g | $1.83 | $3.50 | $1.67 |

| Sweet Condensed Milk | 300 ml | $2.12 | $3.66 | $1.54 |

| Total | $52.41 | $80.99 | $28.58 |

Source: Submitted by an individual from Bath Institution.

Table 4. Price Comparison of Selected Items from a Canteen List

ITEM | PORTION | PRICES | PRICES | PRICE |

| Egg Whites (frozen) | 1 kg | $4.77 | $6.56 | $1.79 |

| Chicken Breast (Halal) | 1 serving | $4.97 | $7.03 | $2.06 |

| Pepper Steak | 1 serving | $5.54 | $7.24 | $1.70 |

| Salted Cod | 1 serving | $7.07 | $10.33 | $3.26 |

| Ground Beef | 400 g | $4.42 | $5.32 | $0.90 |

| Clams | N/A | $1.83 | $3.39 | $1.56 |

| Light Tuna | 170 g | $1.89 | $2.08 | $0.19 |

| White Bread | N/A | $1.89 | $3.10 | $1.21 |

| Tomato Soup | N/A | $1.97 | $2.50 | $0.53 |

| All dressed chips | 150 g | $2.33 | $3.37 | $1.04 |

| Coffee | 200 g | $6.27 | $7.34 | $1.07 |

| Milk | 354 ml | $1.89 | $2.28 | $0.39 |

| Total | $44.84 | $60.54 | $15.70 |

Source: Submitted by an individual from Cowansville Institution.

As previously noted, the incarcerated population is expected to provide or purchase most of their own basic hygiene products (e.g., soap, shampoo) and any additional consumer items (e.g., clothing, footwear, over the counter health and personal products, dietary supplements/vitamins etc.).21 The majority of these products are accessible via the National supplier catalogues that offer a standard list of items. Individuals can buy items with their current account funds, although there are limits to what they can own and the value of all purchased items. The primary national supplier of goods to Canadian penitentiaries is Amazon.22

According to the most recent catalogues (April 2023), incarcerated individuals are offered the same items available in the market at the same prices as any other Canadian citizen. The catalogue also states that prices may change at any given time and it is recommended that individuals account for a minimum of 10% additional funds to their order given the length of processing and the possibility of price changes. My Office conducted a review of the catalogues, and although some items were comparable to general prices on Amazon’s website, the bigger issue is the affordability in comparison to pay. For example, based on the estimates noted above for the average pay at Level C, it would take approximately two full workdays for an incarcerated person to be able to afford a small box of tampons ($5.49 plus taxes and shipping).23 A full pay period would be necessary to cover the costs of shampoo and conditioner ($22.85 plus taxes and shipping).24 and it would take two pay periods to be able to cover the cost of men’s winter gloves ($41.39 plus taxes).25 Prison is already a hardship and though prison life is not meant to be comfortable or easy, deliberately adding to deprivations beyond liberty is counterproductive to rehabilitative aims.

The Deleterious Impacts of Inadequate Pay

Some might ask why persons serving a sentence in a federal penitentiary should be paid at all. There are several reasons to answer this question in the positive and affirmative. Providing work opportunities and adequate compensation provides incentive, helps develop skills and financial literacy, and productively uses their time in the institution. It is, put simply, an investment in rehabilitation and eventual return to the community as a law-abiding person. Reducing the purchasing power of incarcerated persons removes their incentive to work, decreases their quality of life and negatively affects the institutional environment contributing to an underground economy rife with abuse, extortion, muscling and violence. This inevitably leads to spiraling, negative impacts on rehabilitation. Even small debts of $10.00 or $20.00 can have dire consequences in a penitentiary. Limiting access to items for their self-care and the few remaining privileges that make life more tolerable behind bars can further harden and embitter an individual’s outlook on life, inside and beyond prison.

Inadequate offender income also has an impact on the families and loved ones of incarcerated individuals. As we have seen, in the forerunner to the current system, incarcerated individuals were able to save more funds and send income to their loved ones, including support for their children. Part of the purpose was to encourage individuals to budget their income in order to provide financial support to their families. At that time, their wages had comparatively more buying power. This dynamic has shifted considerably in recent years. We have heard several accounts, raised both publicly26 and within my Office, that the families of incarcerated persons, many of whom are struggling themselves financially, have been sending in more money to support their loved one behind bars. In other words, we are now tracking a net flow of monetary contributions into federal facilities, effectively nullifying any of the reintegrative, behavioural or vocational objectives of having a payment and allowance system in the first place.

Beyond life behind bars, an adequate income upon release has clear benefits. Adequate funds for shelter, transportation and necessities can greatly facilitate the transition in the community. Unfortunately, too often, destitution follows individuals from prison to the streets, which serves no public safety interest. Lack of resources upon release remains a significant barrier to remaining crime-free after a period of incarceration.27

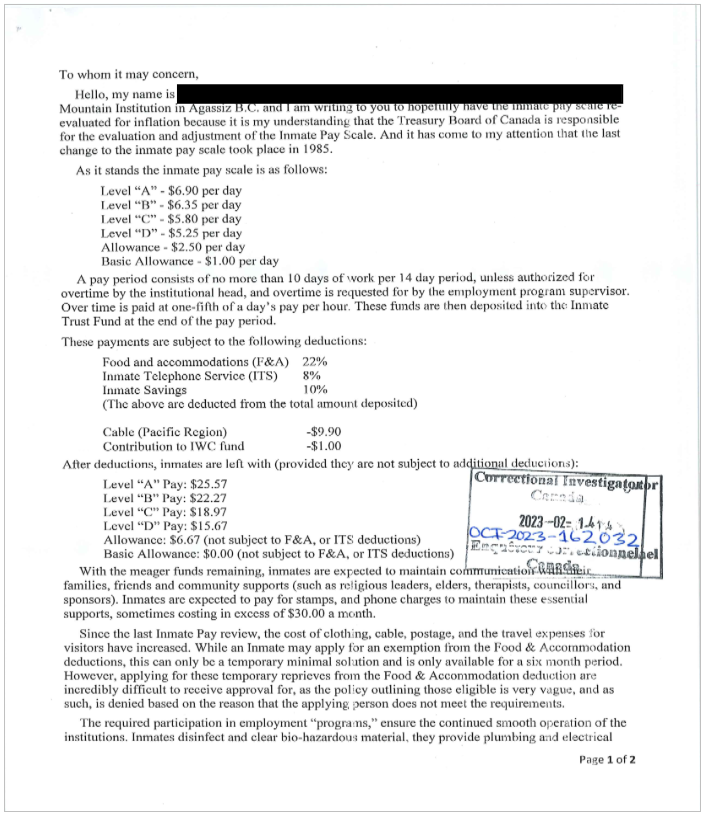

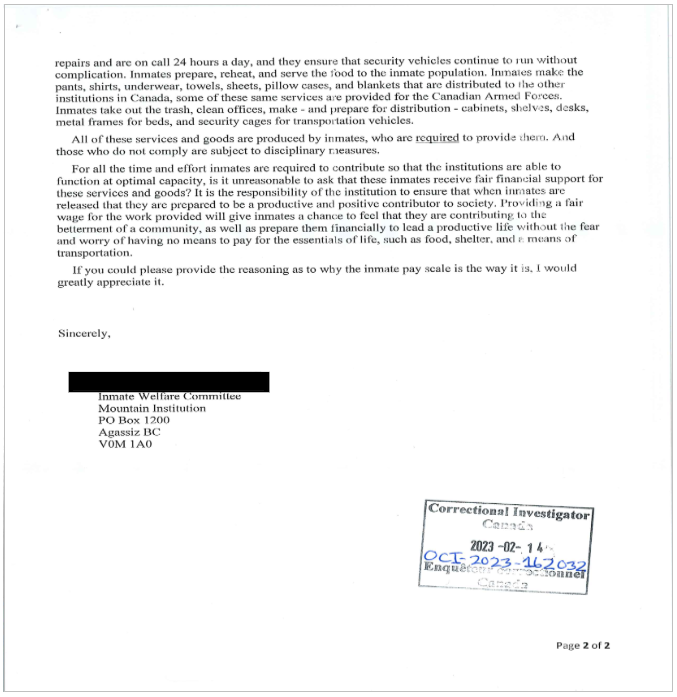

In closing, I have appended a letter from the Inmate Welfare Committee at Mountain Institution, which clearly and effectively articulates the ongoing challenges of rising prices and inadequate pay on the incarceration experience. As my Office has always done, I want to highlight the lived experience of individuals struggling on the inside as they provide invaluable insight and perspective. This correspondence included a letter from the Treasury Board Secretariat (TBS) of Canada, outlining that although TBS is the decision-making body responsible for the approval of the pay scale (pursuant to section 78 (1) of the Correctional and Conditional Release Act), any adjustments would need to be initiated by the Minister of Public Safety.

Recommendations

- I recommend that the Minister of Public Safety initiate an immediate and comprehensive review of the Offender Program Assignments and Inmate Payments system in federal corrections. This review should ensure enhanced pay levels are indexed to inflation to reflect current and expected cost of living increases. At a minimum, I recommend a proposed increase to $3.75 per hour, which reflects the hourly equivalent of the current top daily pay rate of $6.90 (or $1.15 per hour, based on a six hour workday) indexed to inflation going back to 1981. Proposed changes arising from this review should be consulted with the incarcerated population and community organizations serving those behind bars and on parole.

- Until a new payment andcrease the purchasing power of federally incarcerated individuals, including:

- Removing all mandatory deductions;

- Adjusting the pay level criteria to allow for a larger proportion of individuals to receive Level A and Level B payment;

- Ensuring goods that are essential to self-care and welfare (e.g., hygiene products) are provided free of charge; and,

- Reviewing the purchasing catalogue and ensuring goods are more affordable and accessible.

Appendix

Letter from the Inmate Welfare Committee at Mountain Institution and the Treasury Board Response

Thematic Inspection: Dry Cells

Under section 51 of the Corrections and Conditional Release Act (CCRA), the Warden may authorize the use of a ‘dry cell’ when a federally incarcerated individual is believed (on reasonable grounds) to have ingested or concealed contraband in their digestive tract. The practice normally involves strip-searching the individual and placing them in conditions of dry cell detention, which is essentially a barren cell, without plumbing, and under constant monitoring and observation. At many institutions, it is common practice to keep these cells illuminated 24/7. An individual may be placed in a dry cell indefinitely with the expectation that they will eventually ‘expel’ the suspected contraband.

The Office has reported on this issue several times, and I have continued to state that dry cell detention is an incredibly restrictive, degrading, and inhumane procedure for those subjected to it and for staff who must oversee these placements. I have repeatedly recommended that any indefinite placement beyond 72 hours should be prohibited. After three continuous days, it is my contention that this procedure is excessive and unreasonable, if not strictly punitive.

On May 6, 2023, at the time of writing, proposed regulations amending the Corrections and Conditional Release Regulations for dry cell detention were published for public consultation.28 The goal of the new regulations is to reflect proposed changes to the CCRA regarding use of body scanner technology and to establish a framework for dry cell detention “specifying admission criteria, duration limits, and oversight, while also ensuring the consideration of health care needs.”

Upon preliminary review of the proposed regulatory amendments, the Office took note of three key proposed changes to dry cell detention:

1. Body scanner technology: The proposed amendments would introduce new provisions outlining the use of dry cell detention by CSC, including how the implementation of body scanner technology would help the institutional head (IH) in determining if there are reasonable grounds to believe an inmate has ingested or is carrying contraband.

2. Limiting the duration of dry cell detention: The proposed amendments would set a 72-hour maximum for detention in a dry cell. However, the IH would be able to authorize up to two 24-hour extensions of the inmate’s detention in particular circumstances. A dry cell placement may reach a total of 120 hours.

3. Data Collection: Proposed regulations would require that CSC set out procedures for the collection, compilation, management and analysis of data with respect to the use of dry cells in order to identify trends.

Source: Canada Gazette, Part I, Volume 157, Number 18: Regulations Amending the Corrections and Conditional Release Regulations. These new regulations were open for a 30-day consultation with the expectation that the final version be released in Fall 2023, and regulations coming into force in early 2024.

While the proposed regulations were under public consultation at the time of the writing of this report, I would like to acknowledge the intent and direction that they signify. The changes being proposed are consistent with concerns this Office has previously raised in Annual Reports, in particular our repeated calls for a 72-hour maximum cap on dry cell placements. Although our preliminary review of the regulations is promising, the Office intends to provide more in-depth commentary via the formal consultation process.

In the meantime, and as I reported last year, in April 2022, in response to a court order, the Correctional Service of Canada (CSC) issued an interim Policy Bulletin (Bulletin 684) intended to provide “enhanced oversight” and further guidance on the practice of dry cell detention in federal corrections. The changes included new reporting requirements for placement durations that extend beyond 48 and 72 hours (including notice to CSC’s National Headquarters for placements exceeding 72 hours). In August 2022, the Minister of Public Safety issued his own Ministerial Direction (MD) to CSC on this issue to ensure the Service “maintains safe and secure procedures surrounding dry cells, while always respecting the dignity and human rights of inmates.”29 More specifically, the Minister directed that CSC should ensure that placements are as short as reasonably possible. He also encouraged the Service to develop guidelines to prioritize the use of alternative, less restrictive means to detect contraband (e.g., body scanners). Additional Ministerial direction called on CSC to provide “adequate bedding, nutritious food in accordance with the Canada Food Guide, clothing, and toiletry articles and, whenever possible […] access to recreation as long as risks can be mitigated.” Finally, and no less importantly, the MD contained instruction for CSC to report placements exceeding 72 hours to National Headquarters, with daily updates past this point to include the rationale for continuing the placement. Intervention of this kind, at this level, is highly unusual in the history of federal corrections and signifies clear Government intent and expectations in an area that has attracted heightened public and Parliamentary scrutiny.

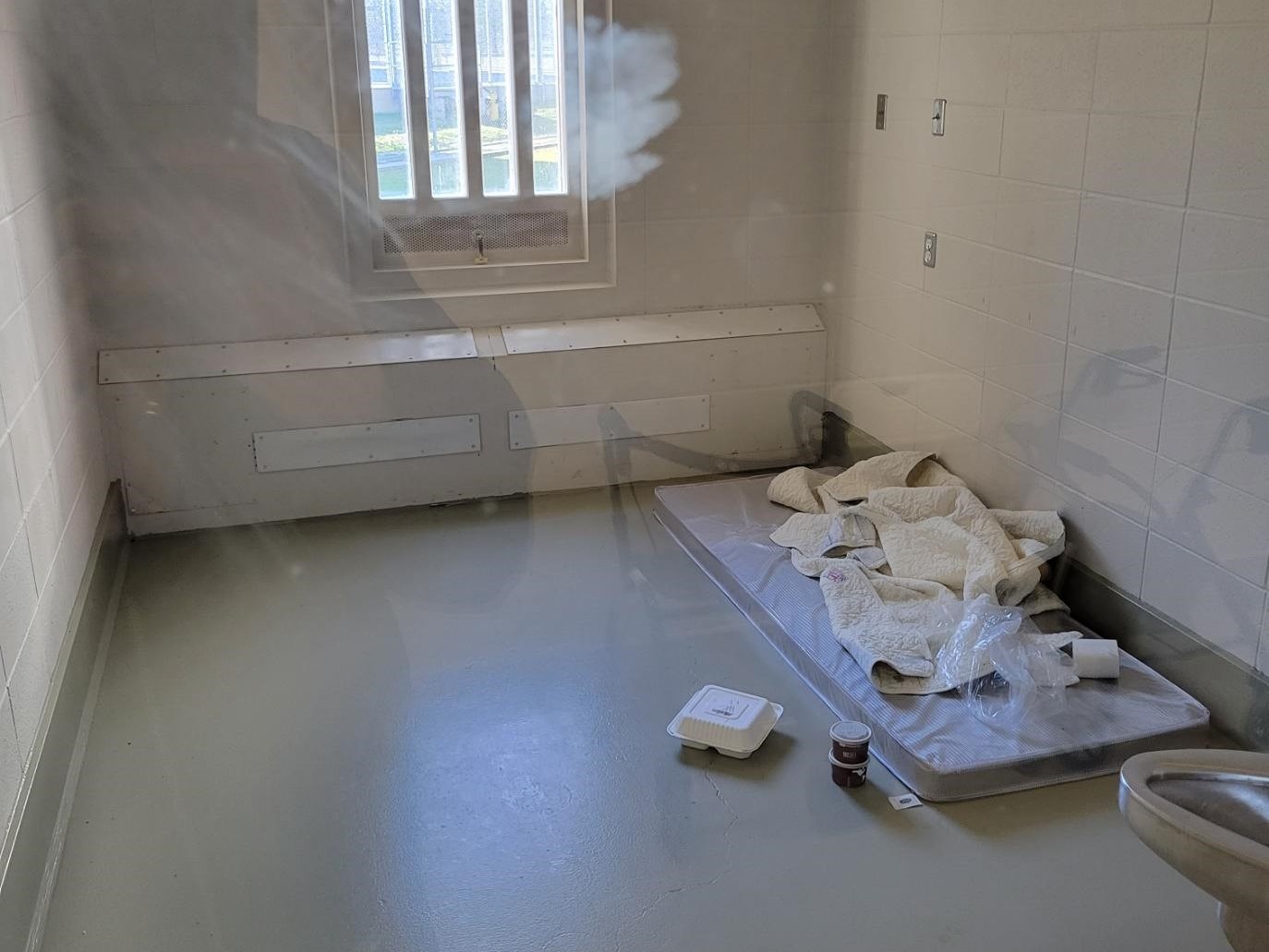

EXAMPLES OF DRY CELL TOILETS

Given our coverage of this issue in last year’s Annual Report and anticipating continuing public and Parliamentary interest in this issue, during this past reporting period the Office conducted a series of thematic inspections and reviews of dry cell placements, criteria, durations and reporting practices. We wanted to assess and report on how newly issued policy and the MD were being operationalized. We made some surprising discoveries based on on-site inspections, review of dry cell placement data, information gathered on institutional practices, as well as documenting the lived experiencesa of individuals who endured periods of dry cell detention extending beyond 72 hours.

Preliminary Review of Dry Cell Data

The Office was able to obtain data on dry cell placements from April 2022 (when the Interim Policy Bulletin 684 was introduced) to December 202230 from Regional Headquarters (RHQ) upon request. Despite CSC implementing changes in 2021-22 to the way in which dry cell placements are documented in the Offender Management System (OMS), the data received was limited with notable gaps, omissions and regional differences in how placements were recorded. Given that institutions did not previously or consistently track and report on dry cell detention placements or durations, this marks the first time the Office has had access to this kind of data. Although we are able to conduct a preliminary review of dry cell detention practices across CSC, it is not possible to compare our findings with previous years or speak to the frequency of usage or duration of placements over time. Our findings are strictly limited in time and context, and must be interpreted in terms of what data and information was provided to us from CSC authorities.

The Office received information on 36 cases of dry cell detention for the eight-month period, from four of the five CSC regions, with one region indicating that there were no placements of 48 hours or more during this timeframe.31 Placement durations ranged from two to 161 consecutive hours. Given that only one region voluntarily provided information for shorter placements (under 48 hours), our analysis was limited to cases where the duration of placements were for 48 hours or more (23 cases in total). Of these, the average dry cell duration across the four regions was 83 hours. More troubling, 13 of the 23 cases involved placement durations exceeding 72 hours. Due to the poor quality and inconsistencies of internal data collection and reporting, it is not clear how accurate or comprehensive this information is. In all likelihood, there are other cases where information about placement duration, rationale, or evidence of contraband were simply never recorded.

Although this information was not initially requested, one region also provided outcome data indicating whether contraband was found or seized for each placement. Results indicated that nearly three-quarters of all cases (including those under 48 hours) did not produce any evidence of contraband, seized or otherwise. Although national conclusions cannot be drawn at this point given the small sample size from a single region, it raises the question of whether this practice has any redeeming value, particularly given the humiliation and degradation for all involved.

Review of Institutional Practices

Since the issuing of the interim policy in April 2022, my team of investigators conducted on-site inspections of dry cell use at ten institutions32 (including representation from all security levels and all five regions). All of the institutions visited had some form of dry celling procedure, including portable methods, static permanent structures, or both. In our findings, investigators noted areas of non-compliance and notable inconsistencies of practices in regards to the availability of Standing Orders33 and the austere conditions of dry cells.

Availability of Standing Orders

All institutions noted the existence of a Standing Order with guidelines for dry cell placements, but few were able to indicate if or when it was last updated and several staff were unclear on standard or expected practices. Based on this finding, my Office reviewed all Standing Orders that were available at the time of writing for 25 institutions and again noted numerous inconsistencies and non-compliance.

Several institutions did not have any Standing Order for dry cell placements, while others were notably out of date (e.g., some were last updated in 2009 and 2013). Multiple Standing Orders provided thorough, detailed information (e.g., specific list of permitted items) while others provided very generic guidance (e.g., ‘adequate’ clothing and bedding) or no instruction at all. There was also inconsistent and incorrect information regarding rules and practices. For example, there were notable differences in instructions around the timing and provision of showers (e.g., daily, every 48 hours or none at all) and only a few Orders mentioned the provision of personal hygiene products, such as toothbrushes. Several Orders specify that telephone contact with family be prohibited, despite this rule not being part of national policy direction.

Overall, the variability in the availability of Standing Orders, the level or lack of detail provided, and the inconsistent and incorrect interpretation and application of guidelines is nothing short of alarming given the especially restrictive nature of these placements.

Austere Conditions of Dry Cells

Given the inconsistencies in institutional Standing Orders, it is not surprising there were considerable differences reported by staff regarding conditions of confinement and provision of mandatory items. Four of the institutions surveyed do not have exterior windows to provide natural light into the dry cells, while half of them are located in the old segregation units. In regards to bedding, some cells are outfitted with a bedframe, while in other cases mattresses are placed directly on the floor. The provision of pillows, bedding and blankets varied from site-to-site, with some only offering security blankets instead of regular bedding, and others not providing pillows. All offenders are required to remove their clothing and are given one of the following options, depending on the site:

- Coveralls

- A security gown

- Underwear and a t-shirt

- Coveralls, underwear, and socks

- Underwear, jeans, t-shirt, and slippers

Staff indicated that individuals receive basic toiletries; however, they are limited in their access to showers, or are not permitted at all.

EXAMPLES OF DRY CELLS

Experiences of Individuals in Dry Cells

The Office heard from or interviewed a number of incarcerated individuals who were dry-celled during the course of this investigation. Their voices have provided valuable insight into the overall experience of dry cell placements. Several individuals referred to their experience as “inhumane and degrading”, noting how humiliating it is to be under constant supervision and monitoring in these facilities. They reported unsanitary and unsafe conditions, describing their cells as “disgusting and repulsive.” Some noted that their cell had not been cleaned prior to their placement (e.g., feces on the walls and toilet, filthy floors under their bare feet, leaking in the cells).

Given the extreme regime imposed by dry-celling, many individuals raised concerns regarding the state of their personal hygiene (e.g., limited or prohibited access to showers, a toothbrush, soap or hand sanitizer), as well as their overall physical and mental health (e.g., inadequate clothing and cold temperatures, sleeping on the floor, no access to recreation and telephones to reach families). Some also noted how their placements seemed unnecessary, excessive or went beyond an acceptable period, despite the presence of mitigating factors (e.g., inconclusive body scans, no indication from drug detector dogs, and multiple bowel movements producing no evidence of concealed contraband).

The Office reviewed an especially egregious case where an individual was placed in a dry cell for more than six days and was subjected to practices that blatantly violated policy. For example, this individual was denied a mattress, and instead was required to sleep on a stack of blankets. They34 were required to wear only a thin security gown but no socks, underwear, or footwear. According to this individual’s statement, they were also required to use the facilities, naked, while under direct supervision of staff, sometimes including staff of the opposite sex. They did not have access to toiletries or hygiene products and they were not permitted to shower throughout the entire six-day placement. Consistent with other complaints, this individual’s cell was freezing, with round the clock artificial lighting that led to sleep deprivation. The conditions were unsanitary and unhygienic (there was no evidence of cleaning or sanitizing prior to or during the cell placement). Among the most troubling aspects was the limited contact with healthcare (limited visits every other day) despite this individual’s requests for medical and mental health assistance, and the institution’s refusal to provide phone access to their lawyer.

DRY CELL TOILETS

Conclusion and Recommendations

Although the newly proposed dry cell regulations offer some promise going forward, for obvious stated reasons reported here, I remain deeply concerned that interim policy and Ministerial directions from 2022 remain, at best, lacking in terms of application and compliance. The prevailing status quo does not bode well for future progressive change in these matters, particularly a time cap on duration of placements. The Office will monitor the implementation of new dry cell regulations and use of body scanner technology as that process evolves. I will also assess how the implementation of new regulations impacts the overall frequency and practice of dry cell detention and how data and information are tracked across the regions. Beyond expectations raised by the proposed regulatory framework, it is clear that some present issues require immediate attention:

- I recommend that the Minister of Public Safety ensure that the new regulations require CSC to report publicly on the frequency, duration and outcomes (whether or if contraband is seized) of all dry cell placements starting in 2023-24, and going forward.

- I recommend that the Minister of Public Safety ensure that the new regulations require the decision to extend a dry cell placement beyond 72 hours to rest with the Regional Deputy Commissioner (RDC). The regulations should state that “under exceptional circumstances” where specific requirements are met, the RDC may extend dry cell placements by each 24-hour period, up to a maximum of 48 hours. Dry cell duration should never exceed five consecutive days.

- I recommend, consistent with the Minister’s Directive, that CSC develop and provide clear, specific, and consistent national guidelines to ensure humane treatment for dry cell placements that includes specific criteria and guidance on items to be provided in terms of bedding and mattresses, food, personal hygiene and toiletries, access to phones, illumination and meaningful human interaction.

National Updates

This section summarizes policy issues or significant individual cases raised at the institutional and national levels over the course of the reporting period. The issues and cases presented here were either the subject of discussions with institutional Wardens, an exchange of correspondence, a follow-up from previous Annual Reports, or an agenda item in bilateral meetings involving the Commissioner, myself, and our respective senior management teams. These areas of unresolved, unaddressed, or updated concerns remain under active investigation. Therefore, this section serves to document progress in resolving issues of national significance or concern.

Patient Advocacy Services in Federal Corrections

On June 21, 2019, Bill C-83 – An Act to amend the Corrections and Conditional Release Act (CCRA), received Royal Assent. In addition to eliminating administrative and disciplinary segregation, Bill C-83 introduced new health care provisions into the CCRA. Section 86.1 of the CCRA formally recognizes the professional autonomy and clinical independence of Correctional Service of Canada (CSC) health care professionals. Section 89.1 requires CSC to provide patient advocacy services to federally incarcerated individuals in order to help patients better understand their rights and responsibilities related to health care. These provisions set out complementary and reinforcing obligations in a correctional health care context.

Recommendations for an independent patient advocacy model within CSC started long before Bill C-83. For example, the concept of an Independent Rights Advisor and Inmate Advocate was outlined in the Ontario Coroner’s inquest into the preventable death of Ashley Smith (December, 2013). My Office has also been calling for the appointment of independent patient advocates for a number of years now, beginning in 2013 and again in 2017-18, “whose role and responsibilities include providing inmate patients with advice, advocacy and support and ensuring their rights are fully understood, respected and protected.” More recently, the Office recommended that, “CSC review independent Patient Advocate models in place in Canada and internationally, develop a framework for federal corrections and report publicly on its intentions in 2020-21 with full implementation of an external Patient Advocate system in 2021-22.”35

Corrections and Conditional Release Act

Patient advocacy services

89.1 The Service shall provide, in respect of inmates in penitentiaries designated by the Commissioner, access to patient advocacy services

- to support inmates in relation to their health care matters; and,

- to enable inmates and their families or an individual identified by the inmate as a support person to understand the rights and responsibilities of inmates related to health care.

Health care obligations

Section 86.1 When health care is provided to inmates, the Service shall

- support the professional autonomy and the clinical independence of registered health care professionals and their freedom to exercise, without undue influence, their professional judgment in the care and treatment of inmates;

- support those registered health care professionals in their promotion, in accordance with their respective professional code of ethics, of patient-centred care and patient advocacy; and,

- promote decision-making that is based on the appropriate medical care, dental care and mental health care criteria.

CSC Actions and Responses to Date

Four years have passed since Patient Advocacy Services were enshrined in law and funding committed for their creation. According to previous CSC responses, implementation of its Patient Advocacy Framework was anticipated to occur by the end of the fiscal year 2022-23, with a commitment towards full implementation by the end of fiscal 2023-24.36 The timeline for the framework has now expired and I have received little indication from CSC that it is willing to move ahead with an independent and external patient advocacy model. Additionally, CSC has previously committed to reviewing Commissioner’s Directive (CD) 800 – Health Services, the organization’s primary health policy document, with the goal of clarifying and strengthening the role of patient advocacy in CSC. I have also yet to see extensive, concrete updates to the policy, despite it being due for review in 2017.37

As I have noted multiple times, independent advocacy is the community standard and patient advocates should be external and functionally independent of the CSC. This is an essential measure for an effective patient advocacy model in a community hospital setting and even more important in a correctional context. An independent advocacy model provides assurance that the rights of patients are protected, patients are provided assistance in exploring available treatment options, and that they fully understand the implications of their decisions.

In response, CSC has consistently stated that all health services staff act as advocates for their patients: “Healthcare professionals, including those providing services under contract, will use their expertise and influence to advocate on behalf of patients for provision of care that advances their health and well-being.”38 CSC has also noted that it facilitates access to provincially appointed patient advocates for incarcerated persons and encourages engagement with non-governmental agencies (e.g., John Howard Society). It is unclear how this works in practice, with some examples noting the challenges of provincial bodies having to take on an oversight role with federal authorities.39 Nevertheless, this does not suffice. A permanent, independent model is necessary.

While I respect that it is the role of every health care provider to be an advocate for their patients, the current health services delivery model is not sufficiently independent and creates an inherent conflict of interest that does not meet the legislative intent of Bill C-83.40 I agree that health care professionals are advocates for their patients and I recognize their tireless work and efforts with a specialized, high-needs population in such a challenging environment. The point of the matter is that CSC health professionals ultimately still work for the Service, even if their clinical independence and professional autonomy are now formally recognized in legislation. An additional layer of oversight is still required to provide support not only for incarcerated individuals, but also for CSC health care staff. A functionally independent patient advocate model is the standard in community hospitals and is a widely accepted domestic and international health care practice. CSC should adopt this essential community standard.

Justifications for Independent Patient Advocacy

Challenges of Informed Consent in a Prison Environment

There are several reasons supporting the need for Patient Advocates to be independent of the Correctional Service. As I have noted before, issues with free, voluntary and informed consent are magnified in a correctional setting. There are numerous scenarios that may impede the independence and capacity of individuals to make informed health care decisions.

In addition to having more demanding physical health needs (higher rates of chronic illness, mental health issues, an aging population), the federally sentenced population is also more likely to struggle with cognitive deficits and learning disabilities (e.g., dementia, Alzheimer’s, ADHD, FASD, intellectual impairment), the impacts of substance abuse, and lower levels of formal education.41 The terms ‘voluntary’ and ‘consent’ can become blurry in an institutional environment where individuals do not have access to other options or other providers, may not fully understand their medical and legal rights and may experience perceived or real undue influence from staff as figures of authority.

Dual Loyalties and Medical Ethics

Whenever health care professionals have to deliver services under correctional authorities, there is an inevitable conflict between the operations of the institutional environment and the medical needs of the patient. Health care professionals in correctional institutions regularly deal with assessing or monitoring individuals who have been subject to use of force, placed in dry cells, or subject to strip searches, etc. These situations put providers in challenging positions of dual loyalty.42

An independent Patient Advocate could provide support to CSC health care professionals in navigating these and other complex issues in corrections, such as the controversial practice of MAiD (medical assistance in dying), or recommending alternatives to incarceration for those in need of palliative or long-term care or whose complex mental health needs cannot be met in a correctional context.

The Office first suggested appointing Patient Advocates to CSC’s Treatment Centres as these are designated psychiatric hospitals where patients can be involuntarily committed, physically restrained for health care purposes, or treated against their will. A penitentiary that can also serve as a hospital is a reminder that consent in the context of corrections is not always free or informed. Many incarcerated patients, such as those at treatment facilities, may not have the required capacity to consent and make decisions about their medical care. A Patient Advocate could help patients and staff navigate these complexities.

Issues with Trust in Health Care Providers

There are also the problems of trust as incarcerated individuals have expressed concerns with, and a mistrust of, prison health care providers. Patient privacy and autonomy is essential in establishing trust between patients and health care professionals.43 However, in a correctional environment, patient-provider confidence is not always practiced as medical staff may need to disclose information or work closely with security staff and prison authorities. It is understandable that a patient may have issues of trust with health care staff who are employed by the same system that imprisons them. This puts an inevitable strain on the therapeutic alliance between patient and caregiver and may exacerbate individual health care needs if incarcerated persons are hesitant to seek medical help or disclose information. Once again, an independent patient advocacy role would help to navigate some of these challenges by supporting incarcerated individuals, from an external perspective, in understanding their rights and options. It would also facilitate health care staff in ensuring the practice of informed consent with third party support.

National and International Models

Although Bill C-83 acknowledges CSC’s obligation to support professional autonomy and clinical independence and that health care professionals should be able to practice without undue influence – these are not clear, enforceable standards. Multiple countries have chosen to transfer the responsibility of health care services in correctional institutions from their judicial authorities to their health authorities, including Norway, France, Australia, and Finland, for example. Despite some ongoing debates as to the placement of authority, some jurisdictions have reported benefits of this independence, such as improved clinical standards and greater transparency and trust.44 Several provinces (e.g., British Columbia, Nova Scotia, Newfoundland, Alberta) have also shifted governance of healthcare in prisons from correctional authorities to their respective provincial health ministries. Alberta also established the Office of the Alberta Health Advocates in 2014 to provide independent advocacy to all Albertans for mental and physical health needs. The Mental Health Advocate (MHA) role, for example, falls under the Mental Health Act to help people who are, or have been, detained in hospital under admission or renewal certificates and people under community treatment order.45

Given the issues raised here, an external and independent patient advocacy model would help bridge gaps in several ways, including supporting incarcerated individuals navigate their health care rights and needs, facilitating CSC health care staff by reducing the burden of dual loyalties and ethical dilemmas and adding an essential layer of advocacy and oversight.

- I recommend that the Minister of Public Safety ensure that CSC take immediate action to develop and implement an external and independent patient advocacy model to provide access to health care advocacy services for all federally incarcerated individuals.

Gender Diversity Policy Review

On June 19, 2017, the Canadian Human Rights Act (CHRA) was amended to add “gender identity or expression” to the list of prohibited grounds of discrimination. Consequently, the Corrections and Conditional Release Act (paragraph 4[g]) provides that the Correctional Service of Canada (CSC) has the duty to accommodate federally sentenced persons based on their gender identity or gender expression,46 regardless of an individual’s physical anatomy or ‘sex marker’ on their identification documents.

The treatment of federally incarcerated gender diverse47 individuals is an issue of increasing importance for the Office and a topic that has been the subject of previous reporting.48 We have voiced concerns regarding institutional placements based purely on anatomy, the need for more consideration for the safety and rights of gender diverse individuals, and the need for a more comprehensive, single point of policy direction on issues related to gender identity and expression.

Since the last time the Office reported on gender diversity issues (2018-19), CSC promulgated Commissioner’s Directive (CD) 100 – Gender Diverse Offenders, in May 2022. The purpose of this CD, which replaced the Interim Policy Bulletin 584, is:

To provide direction on procedural changes that reflect the Correctional Service of Canada’s (CSC’s) commitment to meeting the needs of its gender diverse offender population in ways that respect their human rights and ensure their safety and dignity as well as the safety of others in the institutions and community.

As we have noted, this stand-alone directive is an important step towards recognizing and addressing the needs of incarcerated gender diverse individuals. Its promulgation signifies significant policy, cultural and operational adjustments for CSC’s traditionally ‘sex-assigned’ institutions.

In the coming year, the Office will closely monitor the implementation of CD-100, with the goal of reviewing how these changes translate into action and, most importantly, how they impact on the lived experiences of incarcerated gender diverse individuals. In the meantime, there remain some outstanding areas of concern, specifically:

- need for external expertise on issues of gender diversity in corrections;

- balancing of individual rights and security considerations; and,

- need for safe mechanisms for reporting abuse.

The Need for External Expertise and Specialized Leadership at all Levels

In September 2020, CSC created the Gender Considerations Secretariat (GCS) at National Headquarters (NHQ) to support policy development, implementation, monitoring, and ongoing change management in the areas of gender diversity. Some of their activities include the development of guidance, tools, and training on gender-related issues, and providing recommendations on the management of gender diverse individuals to leadership. Although the GCS has served an advisory role on these issues to a certain extent, there are opportunities to enhance the role of external expertise at the national level. The CD makes no mention of accessing or developing specialized staff on matters related to gender diversity at regional or institutional levels.

Management of issues related to gender diversity requires specific training, skills and experience. Individuals with external expertise on this subject matter should, at the very least, be brought into CSC at the national and regional levels, and designated roles for specialized staff should be established at the institutional level. Greater reliance on external expertise would offer a more informed perspective and help to reconcile the inherently ‘sex-segregated’, operational nature of corrections. For example, the CD currently outlines that all transfers of gender diverse individuals to women’s institutions are to be managed by the Women Offender Sector, while transfers to men’s institutions are managed by the Correctional Operations and Programs Sector. Although the Secretariat is referenced for support on this practice, an established role at NHQ with the appropriate specialization and more decision-making authority would help to bridge that gap, provide a more balanced approach, and ensure consistency of practices.